School Improvement: leaders’ mental models of school improvement

- Caroline Sherwood

- Aug 19, 2024

- 5 min read

I was reminded of Brené Brown definition of leadership following a coaching conversation with the brilliant Sarah Cottinghat (@SCottinghat) - “I define a leader as anyone who takes responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes, and who has the courage to develop that potential” (Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts, 2018). Sarah has been helping me think more intelligently and more strategically about my new seconded one-day-a-week Trust-wide role from September.

What does day one look like?

My new role involves visiting other schools and supporting them with their contextual challenges and problems. One of the areas Sarah has been supporting me with is how to manage the first visit – and, more specifically, that first meeting with the Head Teacher or SLT. Day one needs to broadly do two things:

Make a Connection | Collect Evidence |

Purposefully adopt behaviours which promote trust, reciprocal vulnerability, and a sense of psychological safety. | Systemise the collection of evidence to make a (joint) hypothesis: accurately identify the challenge/problem – and begin planning towards the solution. |

Make a Connection

I understand, from my ongoing experience in the classroom, that when our students believe we want them to succeed – they will work harder and develop resilience when faced with inevitable failure. I feel the same of the adults I work with. As deputy head teacher in my school, I can nurture professionally trusting relationships over time. Stepping into a new school and creating the belonging and connection necessary to work well together is challenging in a different way: I might only work alongside this colleague once a week – or possibly even less. Belonging and social connections are hardwired into our DNA. “Belonging is a close cousin to many related experiences: mattering, identification, and social connection. The unifying thread across these themes is that they all revolve around the sense of being accepted and included by those around you” (Carr et al, 2019). Intentionally fostering trust, vulnerability, relatedness, and psychological safety is essential for our future success together – this knowledge informs the deliberate and purposeful behaviours and language I adopt. This isn’t where I focused the majority of my thinking with Sarah – not because it isn’t important.

Collect Evidence

Developing a systematic and consistent method for collecting evidence during my first visit (that could be utilised in subsequent visits) helps me to ensure I am “identify[ing] a clear priority that is amenable to change” and not “start[ing] with a solution and look[ing] for a problem!" (EEF). Following my coaching sessions with Sarah, I gained real clarity about what this might look like. Interestingly though, our thinking moved to praise.

Positive-negative asymmetry – also known as negativity bias - means that we feel the sting of a failure or criticism more powerfully than we feel the joy of praise. Paired with the fact that “we remember emotive experiences (otherwise known as ‘episodic memory’) better than the hard thinking about tricky abstract concepts… (‘Semantic memory’)” (Quigley, 2024) – the pain and hurt attached to challenges and problems can feel really desirable – and conversations can very quickly focus on them without giving successes time to grow. In addition, both my colleague and I might feel the pull of the problem we want to solve because that is (kind of) why I’m there.

So what role does praise play here? Probably not a big enough one.

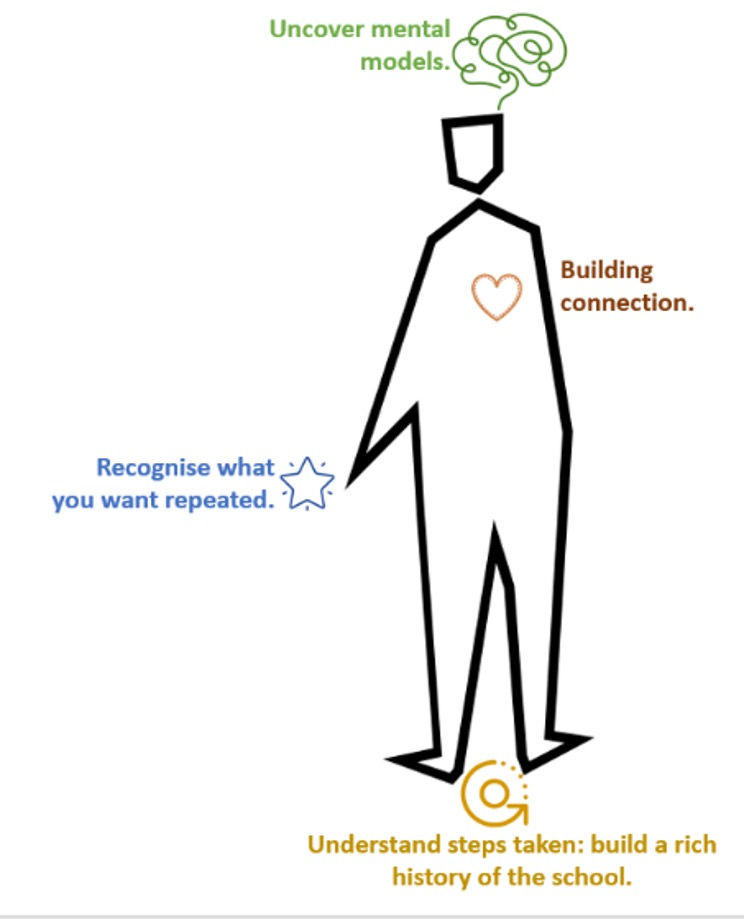

To try and make sense of some of our complex thinking – I created the following model:

When Sarah asked me about why I’d start a conversation with my new colleague focused on what has gone well – I went instantly to: “it is good for our relationship, and it tells me what is going well – we’ll want to maintain this”.

What Sarah had me think about was the leader’s mental models – and she rephrased this moment in the conversation from praise to learning from success.

Learning from success

This reframing is important – this moment in the conversation cannot be a superficial, cursory moment – because we must learn from it. We can’t move on until we’ve learnt something. This reminded me of the change catalysts in Josh Goodrich’s (@Josh_CPD) book ‘Responsive Coaching’ (2024) – the first of which is awareness, the second insights. When we coach teachers, we need to uncover a teacher’s awareness of what is happening in their classrooms and then “help teachers to develop knowledge of important mechanisms of student learning”. This moment in the conversation with my new colleague is also about uncovering their mental model – or insights - and helping them develop knowledge of important mechanisms of school improvement. Just like in responsive coaching, a well-planned question can tell me a lot – if I listen hard enough.

During the learning from success part of our conversation, the following questions might be useful:

What is going well at your school?

How do you know?

What proxies do you have in place?

What are the active ingredients?

Can you tell me why X has been successful?

Talk to me about the cause and effect relationship – what catalysts created the positive outcomes?

What challenges did you face along the way? And how did you overcome them?

Did anything surprise you / was there anything unexpected?

What leadership approach did you choose, and why?

Is this well-established now? Or do you envisage that future adaptations might be necessary? Why?

What these questions should do is

a) ensure this moment in the conversation gets the time it needs and deserves; and

b) helps you to uncover the leader’s mental model.

Recently, Oliver Caviglioli usefully summarised the work of Jean Mandler suggesting that “the structure of schemas is vertical (and hierarchical) while that of mental models (action, in time sequential) is horizontal”

Spending time learning from success means I can learn more about how deliberate the leader’s thinking and actions are; I can begin to understand whether their knowledge is mostly schematic – or whether they have a clear mental model of school improvement. I can slow down their thinking – particularly if the leader’s thinking is so habitual it is difficult for them to break down. I can uncover their schematic knowledge, and what their mental model looks like. Interestingly,

Now, this moment in our first conversation has not only: built a connection, recognised what we want repeated, developed a rich history of the school, uncovered the leader’s mental models – it now has given me the information I need to best work with this leader – knowing that a one-size-fits-all approach won’t work.

Brené Brown says: “I define a leader as anyone who takes responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes, and who has the courage to develop that potential”. By choosing to sit with learning from success and mining this part of the conversation until I learn something, I can (hopefully) begin to take responsibility for finding the potential in people and processes – and develop that potential.

References:

Brown, B (2018) Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. Random House Publishing Group.

Carr, E.W, Reece, A, Rosen Kellerman, G, and Robichaux,A 2019. The Value of Belonging at Work. Harvard Business Review. The Value of Belonging at Work (hbr.org).

EEF, A School’s Guide to Implementation. A School’s Guide to Implementation | EEF (educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk).

Goodrich, J (2024) Responsive Coaching. John Catt.

Quigley, A (2024) Why Learning Fails. Routledge.

Comments