Can We Codify School Improvement? (Part Two)

- Caroline Sherwood

- Oct 6, 2024

- 4 min read

In Part One of Can We Codify School Improvement? I thought about how we can draw parallels with Josh Goodrich’s exploration of the 5 change catalysts in ‘Responsive Coaching’ with how leaders can support other leaders to improve their schools

Next up: insights.

Walking side by side with a school leader means we can learn from each other – we can see through each other’s lens.

Let’s think about a scenario. Trust Lead for Teaching and Learning, Liz, visits a Deputy Headteacher, Richard; a supportive visit – one of many planned for the academic year – where they plan to work together to uncover ways to improve T&L across the school. Liz has spent the first thirty minutes talking with Richard – asking him some great questions (and listening really hard); she feels like she has a growing understanding of his awareness around school improvement and implementation. They now plan on visiting lessons.

The Trust Lead in this scenario should be considering using this time to gain further insights into the school leaders’ awareness – and should be guided by what we know about cognitive bias and biological instincts. Ordinary moments like this – walking the corridors and visiting lessons – often matter more to our success than the big moments and big decisions. Shane Parrish, in ‘Clear Thinking’ (2023), suggests that “in most ordinary moments the situation thinks for us”. Being able to identify bias and instinct can help us see and think clearer.

“Never forget that your unconscious is smarter then you, faster than you, and more powerful than you. It may even control you.”

Cordelia Fine, ‘A Mind of Its Own: How your Brain Distorts and Deceives’ (2007).

Confirmation bias leads people to search for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms their pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses. Essentially, it means you tend to focus on information that supports what you already think and ignore or downplay information that contradicts it. In this way, a school leader’s insights inform their awareness; there are no hard edges between the two – they bleed into one another.

Looking for evidence that confirms what you already think is true, rather than considering all of the evidence available will not lead to the best real-world results.

So, the school leader in this scenario – Richard – might reinforce and strengthen his insights based on what he looks at. And what he looks at is being influenced by his insights.

In addition to this, we’re influenced by biological instincts – and there is nothing stronger. Parrish helpfully defines these instincts as: the emotion default, the ego default, the social default, and the inertia default. The lens in which Richard – our school leader – shows Liz – our Trust leader – around his school is distorted by these defaults. The emotion default means Richard is responding to feelings rather than reasons and facts. The ego default means Richard is reacting to anything on the visit which he feels might threaten his sense of self-worth and position as Deputy Headteacher in the school. The social default means that Richard leans heavily on the norms (both written and tacit) of his school. The inertia default means Richard may be resistant to change – even if he sees the need for it – because he naturally prefers ideas and habits that are familiar and comfortable.

In moments like this, are we thinking under the influence, or are we not thinking at all? Parrish suggests we need to “train ourselves to identify the moments when judgement is called for…and pause to create space to think clearly”. Only then can we examine our own, and others’ insights.

It is important here to remember: Liz is hoping to learn more about Richard’s thinking: his awareness and insights. Not to provide all the answers (although it might be necessary for Liz to do this later in their day and/or relationship).

How might Liz do this?

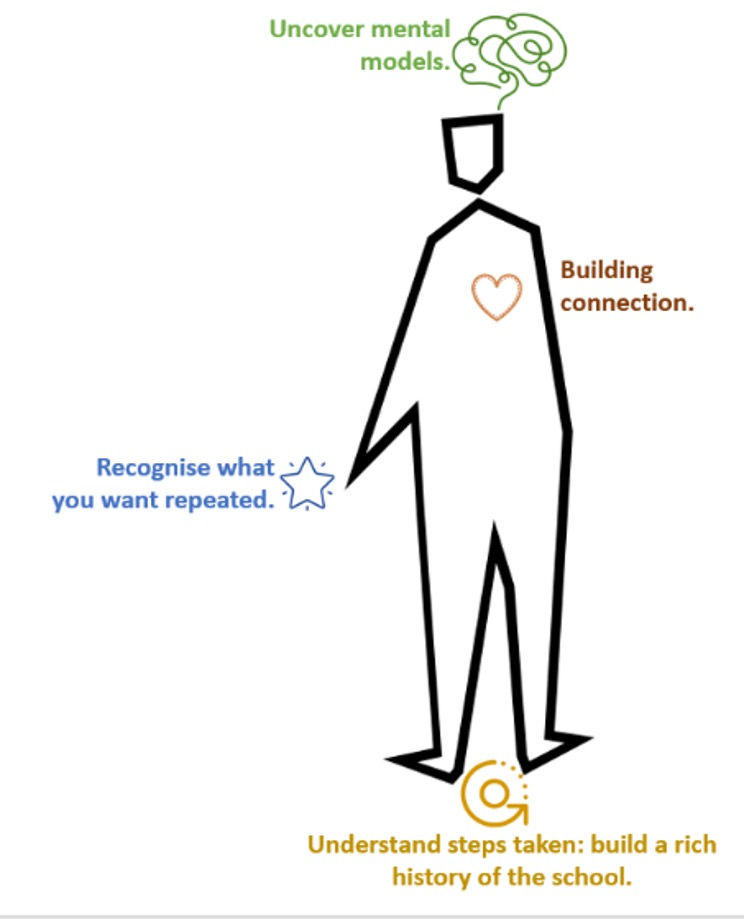

In his recent session at ResearchEd Cornwall, Toby Holland (@MrHo11and) suggests the following questions to uncover teacher’s level of Situational Awareness, using the model below to support his suggestions:

What did you notice within the environment?

What did you understand from that information?

What did you predict would happen next based on that information?

What did you do about it? What decision did you make?

Why did you do that?

How might we adapt these (brilliant!) questions to suit Richard, as Liz tours the school with him?

What did you notice within this/that environment? What can you see based on your experience that someone else might miss?

What did you understand from that information?

What is your understanding based on?

Has this always been your understanding? How has it changed? Are there any gaps in your understanding that you’re aware of?

What do you predict will happen to X if Y continues?

Why are we seeing A, B and C? What decisions/actions/implementation steps have you taken to get this? And why do you want it?

What might be the reason for not seeing A, B or C? Would this be ok?

How do you know X is what is right for your school? Might Y work too?

Perhaps this approach will work towards removing the autopilot and slowing down the thinking. Attempting to remove bias and defaults requires utilising safeguards that render the invisible visible. And we can support each other to do this. Really, we’re aiming to move away from asking questions that require our colleagues to tell us what they think – and instead ask questions which tell us how they think. We can effectively explore their insights – and discover insights into how they’ve reached these insights! An ordinary moment, like walking the corridors with a colleague, becomes an opportunity to gain valuable and meaningful knowledge of the people, the organisation, and implementation.

Comments